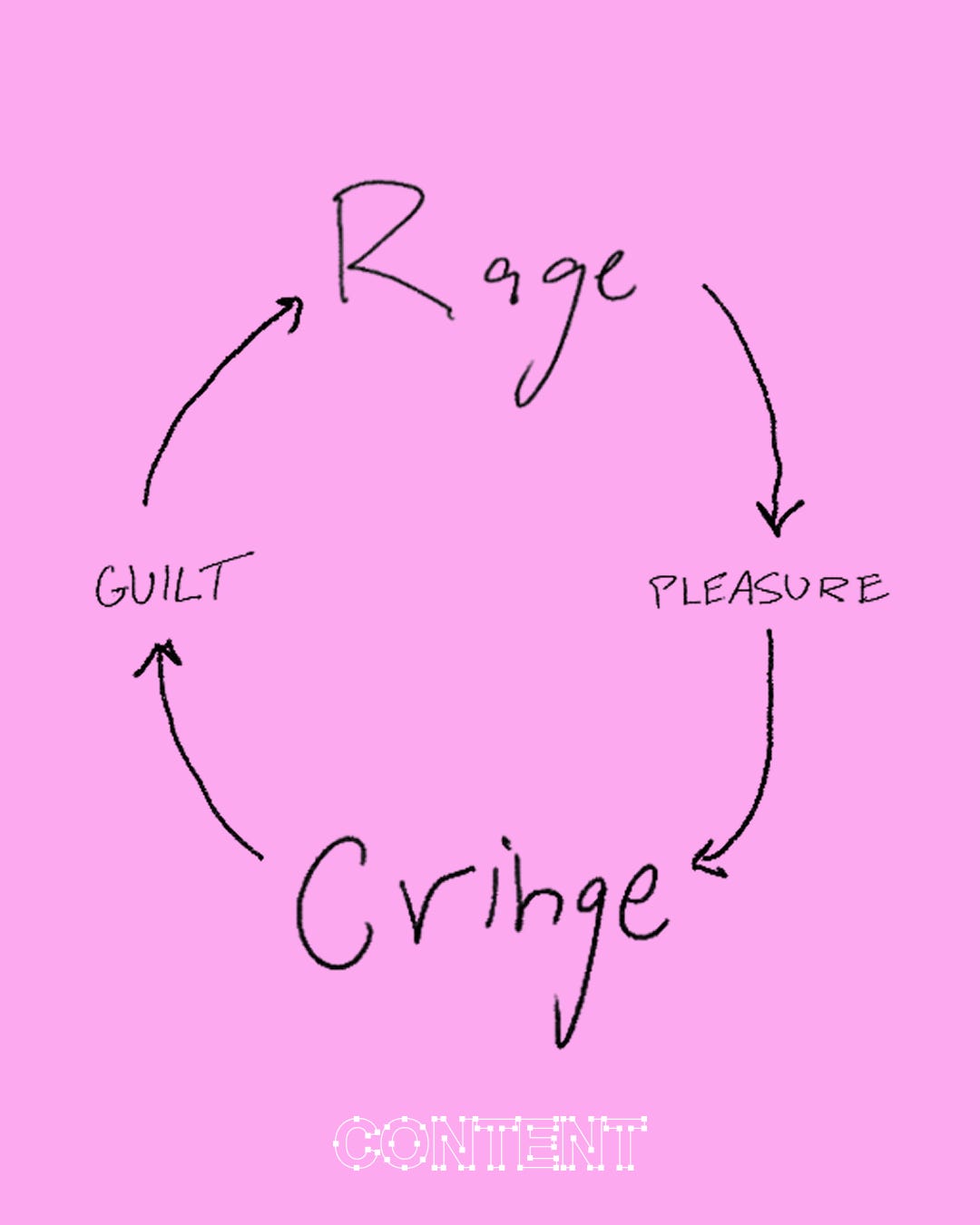

Rage vs. Cringe

Pick your poison...

This is the first edition of my newsletter called CONTENT.

I never totally understood “rage-bait” until I was exposed to the world of bad recipe TikTok. You’ve definitely seen the type of video I’m talking about, the ones where a person with the utmost confidence of a TV chef will put together a wretched culinary concoction and present it as something delicious…Fireball-flavored Pie. A chocolate fountain, but made out of hot dogs and filled with hot dog water instead of chocolate. The most heinous lasagna you could possibly imagine.

If you’ve never seen what I’m talking about then I envy you. Because the worst part about this genre is that once you see one of these videos, you can’t stop watching them. You need to know what other types of culinary war crimes are going to take place next. It’s often even more delightful to do a deep scan on the litany of horrified comments.

That’s the thing about Rage-Bait, it generates unheard-of engagement. It’s bait.

But what fascinates me most about my own experience of internet Rage is it begins negative yet quickly grows into something else. We enjoy things that make us mad the way a dog loves a chew toy. That’s why in professional wrestling you have the archetype of the “heel,” the villain who drives the plot forward through his hate-ability. But what happens to Rage when it's flooded with pleasure? It becomes Cringe, its self-aware counterpart.

Cringe is Rage for the irony-poisoning era. We don’t merely get mad at something Cringe, we observe and enjoy why it sucks from an arm’s length. (Funny enough, the most ecstatic stage of Cringe is when you realize that you, the witness to Cringe, are indeed yourself Cringe.)

Cringe can often be even more engaging to audiences than Rage, because it operates on multiple levels. Those who aren’t in on the joke just get mad — while those enjoying it ironically can make fun of both the content and the NPCs who are mad.

Perhaps one of the most powerful examples of how Cringe can sustain itself is the existence of the television show And Just Like That… There are so many things to hate about the Sex and the City reboot — from its awkwardly aging stars to its tokenized queer and BIPOC characters to its ham-fisted attempts at covering “contemporary topics” — that hating the show out loud became an online sport. It’s now just starting its third season, a milestone few shows on TV ever reach, entirely off the back of cringe-watching.

Yet even Cringe has its limits. As we find ourselves enjoying the process of hating something, pleasure fades to guilt. We feel like the thing that we are cringing at is actually still winning — just by virtue of the fact that it's getting our attention. We feel used and slip back into Rage.

But how is this journey from Rage to Cringe and back again being used to sell products? In fact, it’s most likely an untapped — albeit dangerous and potentially brand-toxic — dynamic.

A couple months ago I scrolled past a curious Instagram ad for a spikey acupressure mat. The picture was of a man lowering himself onto a bed of spikes (I can’t think of a better metaphor for being online in 2025). On top of the image, it reads: “Expensive for what it is.”

Huh? Was the brand’s account hacked? Did some rogue social media manager go postal and put paid ad dollars behind a negative comment? Once you get hooked in by that mindfuck, the caption does a classic copywriting flip along the lines of: “Heck yeah, it’s expensive. Because it’s super well made and we’re an ethical company that pays living wages. And BTW your health is priceless.”

The post had incredibly strong engagement for a paid ad. People who were heated that a spikey mat could cost into three-figures sounded off. Spikey mat enthusiasts defended their beloved spikey mats, while others made fun of the ragers for being so mad. Perhaps most meta of all the commenters were the ones who called out the rug-pull marketing tactic of the post itself.

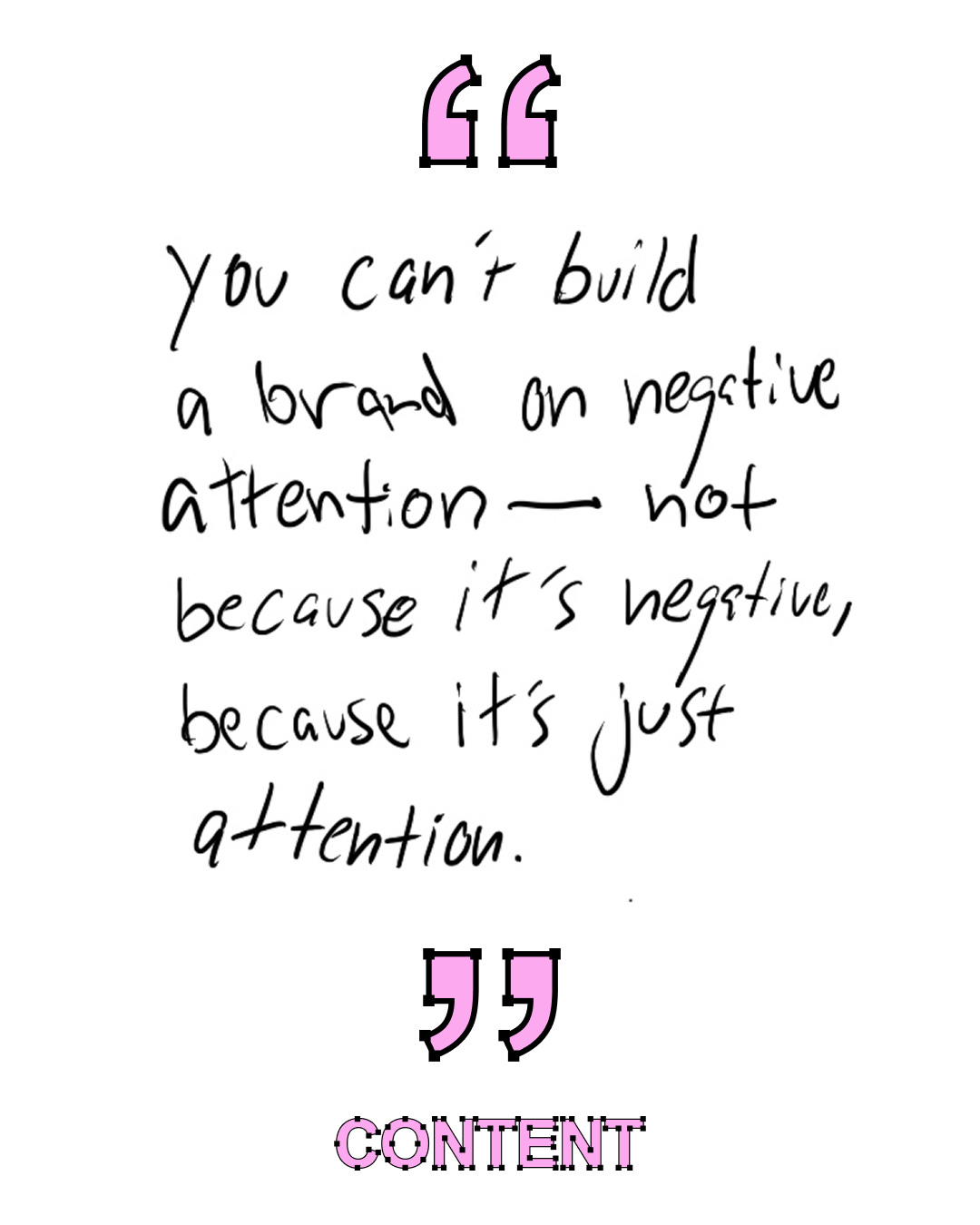

But does this type of Rage dogpile actually sell stuff? I guess you could say that the visibility that comes with engagement inevitably leads more people to seeing the product, and inevitably some of those people will buy it. But you can’t build a brand off negative attention — not because it’s negative, because it’s just attention. Neither Rage nor Cringe produce purchase-intent or community. They’re a collective scream into the void.

In their most overt forms, Rage and Cringe are attention-grabbing tactics that rarely move culture beyond the commotion they make. But if you don’t understand their dynamic, you can end up in the crosshairs. And if used correctly in moderation, they are indeed powerful.

Perhaps the most seminal example of this effect is Hailey Bieber’s infamous Erewhon smoothie. From its inception, the beverage fueled many Rage-tinted questions: What do this Venice Beach health food store and would-be lip gloss mogul have in common? How is it healthy if it tastes like a milkshake? Why is it $20?

Of course, price was the main kernel of rage in this equation (more on that in a bit). But beyond breaking the sound barrier of being a $20 thing served in a plastic cup, there was something inevitable about its success. Even walking up to the counter at Erewhon and dead-panning “One Hailey Bieber smoothie, please” (as I’ve done a dozen times) is a delectably Cringe experience. Many tried it just to hate it, many others ended up going into debt to make it part of their lifestyle. It’s been three years and counting, and the “temporary menu item” is still a phenomenon, and Hailey herself is a billionaire.

What’s perfect about the Hailey Bieber smoothie is that it neither delves too far into Rage nor too far into Cringe — it is suspended somewhere between the two, in a place let’s call The Guilty Pleasure Zone.

In this place, we feel the pleasure that follows Rage without yet feeling the Irony Poisoning that comes with Cringe. Yes, the smoothie is expensive, but so are a lot of things — there’s nothing to get too mad about. On the flip side, it’s Cringe but not so much so that you’re ironically fixated on something you hate. In fact, the smoothie is actually good. So what is there to be too guilty about? And just like that…you’re on Abbot Kinney sipping berry glaze in a serene limbo.

For the luxury world, the biggest source of Rage is often pricing. Luxury items are unbelievably expensive for most people, and when those prices get too high (Himalaya Birkin) or artificially scarce (Labubu), or what the thing actually is seems banal (a white t-shirt), it stirs tremendous Rage. Back when I was the EIC at Highsnobiety during the pandemic, the headline “Check Out This Normcore Sock” would flop — whereas “Check Out This $900 Sock” would do numbers.

Perhaps the master of this was once Demna Gvasalia, who (intentionally or not) drove his work into ubiquity with viral offenses to common sense like his nearly $2,000 purse that looks like a bag of potato chips, or brand new sneakers that look like someone walked through a puddle in them. These items made some online so mad (Rage) and drove others to ironically embrace them as though they are contemporary art (Cringe). But quickly enough, this Rage-Cringe cycle would spin out of control — and Gvasalia would find himself embroiled in a bizarre scandal fueled by … online raging online conspiracy theorists.

I’ve argued to many in private that the Balenciaga scandal was what gave birth to Quiet Luxury. It was a reckoning for those in charge of expensive clothes. Why are we sticking our necks out to be “popular” and “highly online” when our value is actually generated by a small cohort of VICs? Why are we chasing engagement from those who don’t participate in the most important type of engagement of all: buying things? And just like that…fashion became about rich people again.

The stickiness of Quiet Luxury is that from its onset it was able to exist perfectly within the Guilty Pleasure Zone. Our collective fascination with the show Succession was pivotal to its rise in that it added a dose of irony to being rich that made it less Rage-worthy. But Quiet Luxury was never quite so Cringe either. Why? Because dressing more simply and focusing on quality actually looks good on most people.

This summer’s viral The Row flip flops are a perfect exemplar of this. How can a pair of flip flops cost nearly $900? Fair, but they’re also incredibly well-made. Is it Cringe to wear them? Not really, because to the average person you just look like you’re wearing pleasantly generic flip flops. Quiet Luxury’s covertness is another safeguard. A quintessential Quiet Luxury item should just be the expensive version of a normal-looking thing — be it a driving shoe or a cashmere crewneck. This undetectability puts a cap on the Rage or Cringe it can generate.

Funny enough, I think the end of the Quiet Luxury era was signaled by another television show. Or rather, just behind-the-scenes pictures of a television show. Online fashionistas practically stampeded each other to eviscerate images of actress Sarah Pidgeon playing Carolyn Bassett Kennedy in Ryan Murphy’s upcoming FX drama.

For the past couple years, the late CBK and her also late husband JFK Jr. had been resurrected as the patron moodboard saints of Quiet Luxury. Their paparazzi pics oozing with pre-internet 90s innocence and effortless chic were powerfully aspirational. The CBK of FX, however, was a farce of this idea. And it really doesn’t help that proponents of Quiet Luxury are insanely detail-oriented. Her Birkin was perfectly buckled, not open and slouchy in the manner CBK wore the bag (a quirk later on radicalized by both the founders of The Row and Demna too). Her Converse sneakers made no sense. Her clothes looked poorly made. To some it up from a line I’m grabbing from a meme: Wearing beige from Zara does not equal “Quiet Luxury.”

This moment was not merely a roast of someone’s costumes — it brought other questions to the surface: Is this style “exclusive” if every 20-something in the West Village is dressing this way? Why am I modeling my entire personal style after paparazzi pictures of a dead celebrity? Does someone actually look “expensive” when they dress this way, or is it tragically aspirational? In these images Sarah Pidgeon wasn’t just an actress playing an icon — she was our own worst nightmare: a person failing miserably to look chic. Were we Cringe all along?

Sure, this newsletter is about Rage vs. Cringe, but this is just one of many dynamics coursing through the cultural marketplace. If you want to make Content without becoming roadkill, you need to understand these dynamics — how they can propel your message, and how they can upend it. What makes this process hard is that all of these variables are fluid. What’s Based one moment can be Cringe the next. Someone’s genuine fascination can be another person’s nightmare fuel.

In short: It’s all the Rage.

Amazing read, I wish it was longer. This rage-cringe cycle is also really affecting personalities, especially of those that are “chronically online”. When you are constantly aware that liking something is cringe, it changes your personality to be a carbon copy of how other people act (cringe). Then in return, acting the same as everyone else is also cringe (RAGE). The amount of times I’ve been out socializing and someone shares something slightly personal to immediately retract with an apology or saying something along the lines of “omg that was so embarrassing” is becoming exhausting!

On the other hand, when you meet someone who likes the same “guilty pleasure”, an echo chamber of a friendship is created.

Or people who are really passionate about something excuse it for something “neuro-spicy”.

This rage-cringe phenomenon is an invisible beast, quietly weaving its way through all aspects of online and IRL society. Which is why the latest trend is authenticity. My question now is, where are people getting this authenticity all of a sudden! How long have we been hiding? How will this “hiding” transpire in the future?

I am cringe but I am free 🪽